ADVFN, Interactive Investor, MoneyAM, Motley Fool, t1ps.com: financial website entrepreneurs don’t seem to be very good at choosing names. This post tries to do better. It is not really an investment post, except insofar as a start-up with a good name may have a slightly better chance of success than one with a poor name.

A good company or product name should be SUMPIER:

Short

Unique

Memorable

Phonetic

Inoffensive

Euphonious

and (most importantly)

Resonant.

The first four criteria (SUMP) make the name easy, the next two (IE) make it pleasant, and the final (R) makes it potentially great.

EASY

Short A short name facilitates word-of-mouth marketing, forestalls unwanted or ambiguous abbreviations (see the next point) and generally increases salience. But not too short: two or three syllables is probably best, because a stress on one syllable then makes the name more phonetically distinct. This is probably why most letters in the NATO phonetic alphabet used in aviation and maritime radio have two syllables ( A B C D E = AL-FAH, BRA-VO, CHARL-EE, DEL-TAH, ECK-OH).

Unique A name should to be unique in two senses: clearly distinct from all relevant rivals, and not susceptible to undesirable variants (pronunciations, abbreviations or acronyms). Checks on distinction from rivals should include a trademark search. Checks on undesirable variants are less easily systematised. One can quickly rule out rule out Celtic Region Aluminium Products (CRAP) and New United Trading Services (NUTS), but some undesirable variants are less eas to anticipate (see the story about Exxon below).

Memorable This helps recall and word-of-mouth marketing. Memorability is a know-it-when-I-see-it property, but one useful device is alliteration. Toys for Tots, not Toys for Young Children; Leaping Lizards, not Jumping Reptiles.

Phonetic A person who first sees the name in print should be able to tell a friend about it. A person who first hears the name in speech should be able to write it down. In other words, spoken name and spelling should be mutually implicative. Motley Fool is phonetic; ADVFN and t1ps.com are not. Branding consultants seem to have a fetish for odd spellings, capitalisation and even punctuation (del.icio.us, flickr, Yahoo!…), but they all seem obviously unhelpful to me.

PLEASANT

Inoffensive A name should have no unhelpful associations for product or the target customers, either in English or any other customer-relevant language.

Note that this “technical” definition of “inoffensive” does not necessarily exclude risqué names – that could be a helpful association, it depends on the target customers. Some companies do choose edgy names, but they often cause difficulties with distribution, advertising and suppliers. I suspect that for most products, this dangerous game of “niche appeal through offence” isn’t worth the candle.

Under this “technical” definition, most of the financial website names are OK, but Motley Fool is weirdly offensive to its own users. Yes, I know the etymology: the founders were English majors with a penchant for ironic Shakespearian allusions. But that’s too clever: I suspect many users don’t get it, and I think the name is poor.

Inoffensiveness can be hard to verify. When Esso and related companies became Exxon in 1973, the new name had been chosen from computer-generated sequences of letters, and verified as inoffensive in dozens of languages. Within days Exxon had acquired an alternative moniker in the oil industry: it became the double-cross company.

Euphonious A name should sound pleasant. It should be easy to answer the telephone, and easy for people to talk about the company. Motley Fool is euphonious; ADVFN and t1ps.com are not.

GREAT

Resonant This is more subtle, and perhaps more important, than all the criteria above. It distinguishes great names from the merely good.

A resonant name is one which describes, evokes or emphasises either or both of:

(a) the benefits of the generic category (product resonance)

(b) the comparative advantages of your specific offering (brand resonance).

Resonance can come either from the name’s literal meaning (denotation) or associations (connotation).

Examples of names with product resonance: eBay, Match, Rightmove, Twitter, uSwitch, Youtube.

Examples of names with brand resonance: Betfair, Costco, Dulux, Easyjet, Topshop, Valu-mart.

As these examples show, product resonance tends to be more important when a company is creating an entirely new category, and brand resonance when a company is entering an existing category. In my view, none of the financial website names has much of either type of resonance.

The ideal is to have both product and brand resonance in one short name, but this is almost unachievable (I find it hard to think of examples, although perhaps Betfair is close). More achievably, a name with product resonance can be supported by a strapline or slogan with brand resonance, or vice versa.

EVALUATING FINANCIAL WEBSITE NAMES

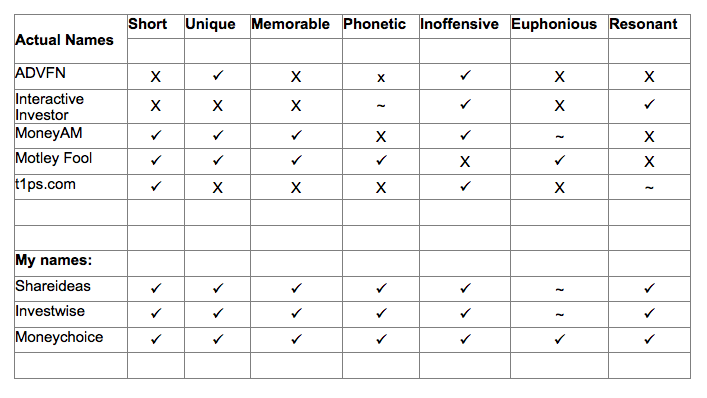

For financial websites, the following table evaluates some extant names against these criteria, and also some hypothetical names (tick = positive, X = negative, ~ = neutral or hard to say).

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Grammatical convertibility Conversion refers to the ability of a word to function in different parts of speech (also called zero deviation or functional shift). It helps if the company or product name (a noun) satisfies most of the earlier criteria when used as a verb. The dominant search engine got this right (“Let’s Google him”); competitors that fell by the wayside often didn’t (Let’s AltaVista him” or Let’s AskJeeves him”).

Category name versus brand name The category name is the generic description; the brand name (protected by trade-marking) is your specific product. Generally, you want these to be clearly different. So if your product is entirely novel, it may be a good idea to invent a category name as well your specific brand name.

Examples of category names v. brand names:

Vacuum cleaner v. Hoover

Personal organiser v. Filofax

Betting exchange v. Betfair

If you don’t create a distinct category name, customers may create one you don’t like. Alternatively, your own brand name is at risk of being used by customers to refer to competitor products. (Obvious exception: if you are a latecomer copycat, you may want customers to corrupt the dominant brand name in this way.)

Narrow versus broad names A narrow name alluding to the company’s initial product or geographical location may give good initial resonance, but also act as an obstacle to later expansion. Be careful not to be too specific.

Domain names The discussion above assumed a unique and hence new name, for which a corresponding domain is likely to be available, but obviously this needs to be checked. Any similar domains – for example slight misspellings of the name – also need to be checked (and acquired, before somebody else does).

Book names Similar criteria can be applied to choosing book titles. I think the title of my book Free Capital satisfies the criteria above, except for one drawback: it isn’t resonant – or even comprehensible – until after you’ve read the book. Hence the sub-title How 12 private investors made millions in the stock market, which I hope gives some prospective resonance.

Finally, I acknowledge that many companies do succeed despite the handicap of poor names against the above criteria. Yahoo!, GoDaddy, Digg…these all seem to me to have no category or brand resonance, and foolishly indulgent spelling, capitalisation or punctuation. But a poor name makes life unnecessarily difficult. Why not try to get it right?

Update (10 Jan 2025): Aswath Damodaran on the value of brand names.

Update (1 May 2025): Choosing baby names.